Fantastic Animals and the Art of Science Communication

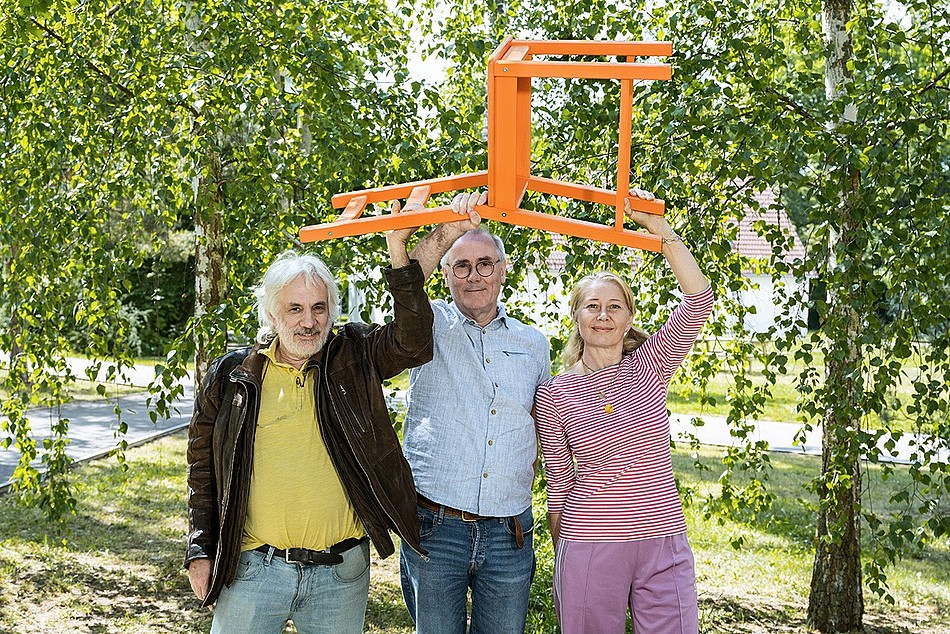

Stiftung Charité has been funding science x media Tandems as part of its Open Life Science program since 2023. Every year, it supports collaborations between scientists and media professionals on innovative projects designed to promote science communication. Professor Gary Lewin and science communications trainer Russ Hodge at the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine (MDC) joined forces with the Berlin artist Kat Menschik in the first cohort of the science x media Tandem program. Together, they worked on an ambitious project that culminated in the popular science book “Masters of Survival: On Freeze-Resistant Fish, Radiation-Resistant Tardigrades, and Self-Healing Amphibians” (2024) published in German by Galiani Verlag. The book tells us what extraordinary animals can teach us about being human and about the impact of climate change and biodiversity loss on humans, animals, and the environment. We met with the team at the MDC campus in Berlin-Buch to the north of the city to discuss their work.

How did the three of you – a scientist, an award-winning illustrator, and a science communications trainer – come together? Who had the idea for the project and what was the motivation behind your rather unusual collaboration?

Menschik: We first heard of each other through a mutual friend, Salim Seyfried, Professor of Animal Physiology at the University of Potsdam. He told me about some colleagues who were looking for an artist for a science communications project. Although I was pleased to have been asked, I initially declined as I was fairly booked up for the year. But when we met for dinner a little while later, he mentioned that it was a project about animals – now I was listening. I was also a bit annoyed – why hadn’t he told me that earlier?! Drawing animals is one of my greatest passions. Once I had spoken to Russ on the phone, I needed no more convincing, though we had just one week to go before the deadIine! (laughs)

Hodge: Gary laid the foundations for our project in 2019 with an academic conference about his research on the naked mole rat as a model organism for extreme physiology and work on other ‘unusual’ animals.

Lewin: Yes, it was called ‘Beyond the Standard: Non-Model Vertebrates in Biomedicine.‘ The original idea came from Alison Barker and Jane Reznick, two of my postdocs at the time who now lead their own research groups in Frankfurt and Cologne. All three of us are fascinated by what are known as ‘non-model organisms’, that is, organisms which are not normally considered relevant in biomedical research. We felt that focusing on just a handful of standard models overlooks so much of our planet’s incredible biodiversity, especially when it comes to animals which adapt to their environment in sophisticated and often rather unusual ways. We wanted to take these animals into consideration, so we issued a call for papers which asked: What lessons can we learn from remarkable animals in biomedical research? The conference ended up being one of the best I have ever attended. The enthusiasm was palpable: it was an opportunity for scientists who might not otherwise encounter one another to exchange ideas. We had people working on pythons, fish, whales, and dolphins – and for two or three days they were all gathered in one room.

Funding program

science x media Tandem Program

Tandem partner

Kat Menschik

Funding period

2023 to 2024

Specialism

Neuroscience, Somatosensation

Project title

What remarkable animals can teach us about being human

Institution

Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine (MDC)

2021 – 2025

Co-Speaker Molecular Processes and Therapies Program at the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine (MDC)

2003 – present

Group Leader, Department of Neurobiology, MDC

2003 – present

Professor for Medical Genome Research in the Faculty of Human Medicine at Freie Universität Berlin (later transferred to Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin)

Hodge: I do a bit of art on the side, so back then Gary asked me if I could draw the animals discussed at the conference. I said of course, and got to listen to lots of the talks as a result. It was all absolutely fascinating. I had been thinking we ought to do something bigger with it for years, so when Stiftung Charité announced its science x media funding program I thought: this is our chance! It would have been a very unusual project for the MDC alone as we generally do more traditional science communication – but this funding suddenly enabled us to take a bit of a risk and brought us the necessary resources too! We were delighted to find a renowned publisher in Galiani Verlag who went down this path together with us. The result is a lavish, beautifully designed book that does justice to both the art and the science.

You mentioned model organisms – could you briefly explain what they are in lay terms?

Lewin: The animals most commonly used in biomedical experiments today are drosophila (fruit flies), worms, zebrafish, and mice. Ninety-nine per cent of biomedical research is conducted on these four model organisms. Practically all the Nobel prize winners over the last two or three decades have used them, and not without reason: they are ideally suited to genetic manipulation. You can turn off or alter almost all their genes, their development is well understood, and they are cheap to look after. But at the same time, this overlooks much of our fascinating biodiversity.

What was the fundamental communication need that you wanted to address? Why was it important to you to tell the public about this kind of animal-based research?

Hodge: Even at the original conference I was struck by how open minded the scientists were towards animals and how much they cared about the ones they researched. Animal welfare is of course an important social issue, and as we gain ever more scientific advances and new technologies, the question of whether it’s at all necessary to use animals in research is becoming more and more relevant. In some cases, we can now use artificial systems to reduce some of that work. But those who conduct research with unusual animals pose questions that go beyond those typical of biomedical science, or what the public might expect. For one thing, many illnesses which plague humans, such as cardiovascular disease, also occur among animals. And some species have already solved these problems through evolution. Giraffes, for example, do not suffer from high blood pressure, despite the enormous pressure needed to pump blood several meters up to the brain. How is this possible? And what lessons can we learn?

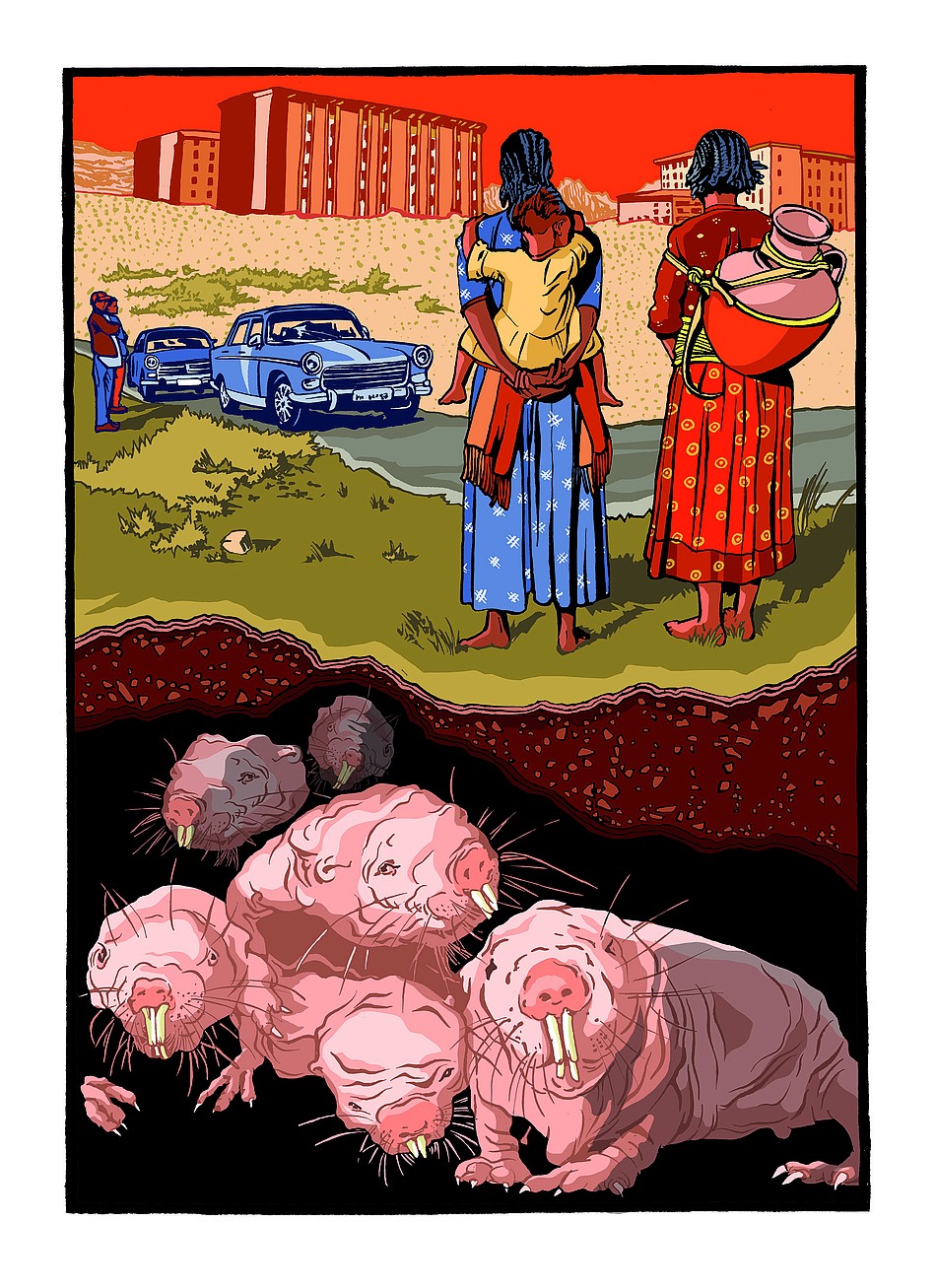

Lewin: These researchers – myself included – are fundamentally interested in the diversity of life. We consider the animal as a whole, not just its constituent parts. We want to understand how everything is interconnected. Creatures that live underground like the naked mole rat have completely different metabolic needs and a different sensory understanding of the world. They don’t need eyes and navigate using their sense of touch or smell instead. This is extremely relevant for research into the (non-)existence of pain. Naked mole rats can also survive on almost no oxygen, whereas we humans immediately suffer distress without it. It’s fantastic that the metabolism can function on such minimal resources when living underground. I’m motivated by the earth’s biodiversity as I believe that we can learn from animals, especially other mammals like the naked mole rat. We wanted to use the tandem to share our holistic attitude towards such remarkable adaptations and the scientific interest which motivates us with the general public.

In “Masters of Survival” you not only tell the stories of remarkable animals, but also of the people who research them and the precarious conditions in which they often find themselves, as well as the professional networks and the stroke of luck that is sometimes needed for such research. Russ Hodge, how did you go about making the science and its backstory accessible to a wide audience?

Hodge: Traditional science communication which is the ‘daily bread’ at the MDC and most other institutes usually involves publishing concrete results as soon as possible after a discovery has been made – for example, in press releases. Writing a book was an opportunity for both me and the scientists involved to step back and reflect. Researchers usually communicate in a very precise way which is predominantly directed at others within their own circles of expertise. They get few opportunities to tell their own stories, such as how their own lives have become interwoven with the fate of a particular animal. That’s why I tried to let them speak for themselves and depict them as individuals. Most people outside science don’t have much contact with that world – before I started working in science communication, for example, I didn’t really know any researchers. As an outsider, you quickly get the sense that academia is a closed shop, and so I set about making these people seem more approachable, showing them for who they are as human beings and trying to convey how they think beyond just their work.

Menschik: I can’t emphasize enough just how special Russ’ idea behind the texts is. I’ve never seen or read anything like it. The interweaving of human and animal stories and their respective contexts is what makes this book so vivid.

Hodge: The writing process was demanding as I hoped to reach a really broad group of readers and didn’t want to presume they would have any pre-existing knowledge of biology. This meant that I had to introduce every single concept, but without repeating myself too much in each chapter. As popular science writers, you can draw on everyday analogies and images to make even very complex scientific ideas clearer to the reader, we have a pretty big toolbox to do this.

“Masters of Survival” doesn’t depict animals in isolation against a white background: they are instead embedded within their environment. Kat Menschik, how did you approach the task of illustrating Russ’ writing?

Menschik: I wanted the large-scale illustrations to reflect Russ’ vivid storytelling. With the naked mole rats, for example, Gary describes what the world looks like above the ground in which they live in Africa. I found this absolutely fascinating and challenged myself to depict the entire scene in a single picture – stretching from the sky to the subterranean world. I was also inspired by the old educational diagrams and the display cases you see in natural history museums. With ‘Masters of Survival’, we wanted to create a book that is reminiscent of an old encyclopedia with hand-drawn diagrams. As a child, I loved looking at the plates in the old Brockhaus encyclopedias. These large illustrations take a lot of effort to draw, but I’m so pleased they worked out. As an artist, I have times when I worry that I might have run out of ideas and that the newspapers will say I’m repeating myself! Musicians know it as the fear of the second album. Luckily I was able to get past it here!

Lewin: Science and art are closer than many people think. In fact, scientists face the same fear: it’s important not to repeat yourself and to stay original.

Moving on to a different topic: academic freedom is under threat across the world and securing research funding is becoming more difficult in these uncertain times. Would you say that science communication and advocacy are needed more than ever?

Lewin: Absolutely, although the nature of this advocacy is currently inadequate – at least when it comes to politics. Research already has an enthusiastic audience: I’d even go as far as to say that this is the silent majority in society. The loud voices against us often come from very small groups which mainly exist online, and yet they are able to exert a huge amount of political pressure. Meanwhile, the German parliament overlooks organizations like patient self-advocacy groups, in my view. But these initiatives are key in highlighting the essential role played by the life sciences, without which we would not have medicines to cure disease or ease pain. Even when the journey to develop a new medicine often begins twenty or thirty years earlier with the decoding of an important mechanism upon which the translation of the basic research hinges.

Hodge: That’s why the kind of stories we tell in “Masters of Survival” are so important. Most scientific advances are long in the making. A popular science book is a good medium for us to cover more of the history of science than other types of texts, and you bring people closer to many important developments and put them into context. Few other formats allow you to tell such complex stories: you could do so with a chapter in a book, or an article in the New York Times, The Washington Post, or Scientific American. Overall, it’s incredibly important to consider how any particular discovery comes across as a whole. But very few people have the endurance for long, dry texts. That’s why we try to captivate our readers with images and text, to keep them gripped by the story. This was the motivation behind our joint efforts in the tandem project.

Now our time is nearly up, I’d like to close with a question that requires a one-word answer. What’s your favorite animal? I think we might already know Gary Lewin’s one…

Lewin: No! (smiles) Aardvarks are my favorite!

Menschik: I’d say pangolins!

Lewin: Oh yes, they are beautiful too.

Hodge (after long deliberation): Giraffes! But as a writer, you develop an intimate relationship with all of your ‘characters’ – in this case, all the animals and the people studying them.

Dr. Nina Schmidt

May/June 2025